VINTAGE PICTURES

The cover art of Frank Schoonover

The cover art of Frank Schoonover

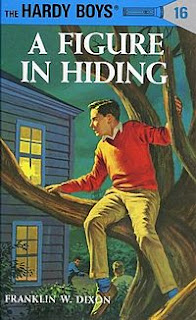

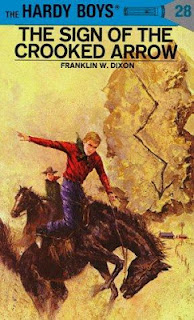

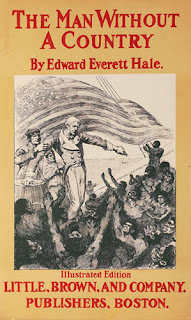

The proof of the book is not only in the reading. It is also in feasting the eyes on the cover. Particularly, if the art is by an illustrator like Frank Earle Schoonover (1877-1972).

Schoonover, one of the foremost students of renowned illustrator and author Howard Pyle, had more than 2,000 illustrations to his credit and many of these adorned the dust jackets of well-known books and magazines that included stories of Hopalong Cassidy by Clarence E. Mulford, A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs, and Blackbeard Buccaneer by Ralph Delahaye Paine.

Schoonover, one of the foremost students of renowned illustrator and author Howard Pyle, had more than 2,000 illustrations to his credit and many of these adorned the dust jackets of well-known books and magazines that included stories of Hopalong Cassidy by Clarence E. Mulford, A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs, and Blackbeard Buccaneer by Ralph Delahaye Paine.

|

| Hopalong Takes Command oil on canvas by Schoonover for The Fight at Buckskin story (1905). |

Schoonover worked in his studio in Wilmington, Delaware, where he earned the title of the Dean of Delaware Artists. His art collection, pertaining mainly to the early 20th century period, is preserved at the Delaware Art Museum. The museum was founded in 1912 as the Wilmington Society of the Fine Arts in honour of Howard Pyle. It celebrated its centennial last year.

According to the Schoonover Studios Ltd, “Schoonover’s subject matter included cowboys, Indians, and Canadian trappers. His forms were simple and well defined and his moods powerful. Later in his career, his style became less rigid and more impressionistic. Schoonover was also an accomplished water colourist and muralist and an avid photographer. He used photographs as references for his illustrations to remind himself of the mood and character of the models.”

According to the Schoonover Studios Ltd, “Schoonover’s subject matter included cowboys, Indians, and Canadian trappers. His forms were simple and well defined and his moods powerful. Later in his career, his style became less rigid and more impressionistic. Schoonover was also an accomplished water colourist and muralist and an avid photographer. He used photographs as references for his illustrations to remind himself of the mood and character of the models.”

The Golden Age illustrator was born in New Jersey, educated at Drexel University, Philadelphia, and died in Wilmington at the age of 95.

You can learn more about Frank Schoonover at Schoonover Studios Ltd and the Schoonover Fund.

You can learn more about Frank Schoonover at Schoonover Studios Ltd and the Schoonover Fund.

Pictures: © Wikimedia Commons