FILM REVIEW

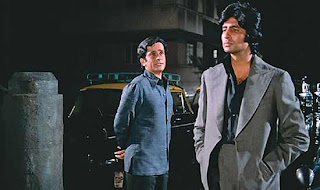

Sidney Poitier in

In the Heat of the Night

The first thing that strikes you about Sidney Poitier, irrespective of which of his films you are watching, is his steady gaze and unblinking eye. It makes you uncomfortable even if you are nowhere in his picture. If you play who-blinks-first with one of America’s most intense-looking actors, you’ll blink first. I bet he can stare down an owl. It’s a look Poitier has patented in reel life and, I suspect, in real life too. It sits easily on his face.

It’s this unwavering eye that greets small-town police chief Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger) who hauls up Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier) and pins a high-profile murder on him, which goes well with the tagline—“They got a murder on their hands. They don't know what to do with it.” If you don’t catch the culprit, within twenty-four hours of the murder, you fabricate one, like evidence.

Tibbs, a seasoned homicide detective from Philadelphia, is passing through the town when Gillespie orders patrolman Sam Wood (Warren Oates) to arrest him for the murder of a prominent businessman. The police chief is under pressure, as they usually are, to nail the killer–pronto! And so he nails Tibbs without realising who Tibbs is.

Detective Tibbs is let off the hook early on in the film, as the police chief reluctantly calls up his boss in Philadelphia and confirms that he is, indeed, whom he claims to be–a crack homicide sleuth. Gillespie then, equally reluctantly, enlists his help to solve the murder case.

In arresting the detective, Gillespie jumps the gun on two counts: one, to prove he is worthy of his badge, and two, he is prejudiced against blacks. There is an undercurrent of racial tension throughout the film.

But then, racism is a recurring theme in Poitier’s films, notably To Sir, with Love (1967) in which he disciplines an unruly class of largely white students, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967) which touches upon the bold subject of interracial marriage at a time when it was outlawed in several US states. In In the Heat of the Night, for instance, Tibbs gets into a lot of trouble, often at the risk of his own life, when he suspects Eric Endicott (Larry Gates), a powerful man in the county.

Tibbs and Gillespie work together and as they make progress, they develop respect for each other, eventually resulting in friendship between the two policemen. Tibbs, of course, hunts down the real killer in the end.

For me, there are two highlights in this movie. One, when Endicott slaps Tibbs for attempting to interrogate him and Tibbs slaps him right back (that one scene sent a powerful message of racial equality during a tumultuous period in US history–the African-American civil rights movement); and two, Detective Tibbs’ unwavering courage in the face of stiff resistance and, more importantly, the manner in which he extracts respect from the very people who were going to incarcerate him.

The Academy Award winning In the Heat of the Night, directed by Norman Jewison in 1967, is based on the book by John Ball. A must-see.

For more overlooked/forgotten films and a few other reviews, visit Todd Mason's blog at http://socialistjazz.blogspot.com

The first thing that strikes you about Sidney Poitier, irrespective of which of his films you are watching, is his steady gaze and unblinking eye. It makes you uncomfortable even if you are nowhere in his picture. If you play who-blinks-first with one of America’s most intense-looking actors, you’ll blink first. I bet he can stare down an owl. It’s a look Poitier has patented in reel life and, I suspect, in real life too. It sits easily on his face.

It’s this unwavering eye that greets small-town police chief Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger) who hauls up Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier) and pins a high-profile murder on him, which goes well with the tagline—“They got a murder on their hands. They don't know what to do with it.” If you don’t catch the culprit, within twenty-four hours of the murder, you fabricate one, like evidence.

Tibbs, a seasoned homicide detective from Philadelphia, is passing through the town when Gillespie orders patrolman Sam Wood (Warren Oates) to arrest him for the murder of a prominent businessman. The police chief is under pressure, as they usually are, to nail the killer–pronto! And so he nails Tibbs without realising who Tibbs is.

Detective Tibbs is let off the hook early on in the film, as the police chief reluctantly calls up his boss in Philadelphia and confirms that he is, indeed, whom he claims to be–a crack homicide sleuth. Gillespie then, equally reluctantly, enlists his help to solve the murder case.

In arresting the detective, Gillespie jumps the gun on two counts: one, to prove he is worthy of his badge, and two, he is prejudiced against blacks. There is an undercurrent of racial tension throughout the film.

But then, racism is a recurring theme in Poitier’s films, notably To Sir, with Love (1967) in which he disciplines an unruly class of largely white students, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967) which touches upon the bold subject of interracial marriage at a time when it was outlawed in several US states. In In the Heat of the Night, for instance, Tibbs gets into a lot of trouble, often at the risk of his own life, when he suspects Eric Endicott (Larry Gates), a powerful man in the county.

Tibbs and Gillespie work together and as they make progress, they develop respect for each other, eventually resulting in friendship between the two policemen. Tibbs, of course, hunts down the real killer in the end.

For me, there are two highlights in this movie. One, when Endicott slaps Tibbs for attempting to interrogate him and Tibbs slaps him right back (that one scene sent a powerful message of racial equality during a tumultuous period in US history–the African-American civil rights movement); and two, Detective Tibbs’ unwavering courage in the face of stiff resistance and, more importantly, the manner in which he extracts respect from the very people who were going to incarcerate him.

The Academy Award winning In the Heat of the Night, directed by Norman Jewison in 1967, is based on the book by John Ball. A must-see.

For more overlooked/forgotten films and a few other reviews, visit Todd Mason's blog at http://socialistjazz.blogspot.com