Superman, Batman, Spider-Man, Daredevil, The Hulk and Iron Man…

These are the initial six superheroes from the DC and Marvel stables whose transformation from their first comic book appearance decades ago (covers on the left) to their big screen debut decades later (posters on the right) has left readers and viewers asking for more.

The box office craze for superhero movies started with Richard Donner’s Superman in 1978 where the late Christopher Reeve played ‘The Man of Steel’ to perfection. He was equally convincing as Superman in the three sequels that followed even though the storylines did not match up to his super feats. Brandon Routh acted well in Superman Returns in 2006 but was nowhere close to Reeve’s portrayal of Clark Kent/Superman—a role that began and ended with Reeve. R.I.P.

The box office craze for superhero movies started with Richard Donner’s Superman in 1978 where the late Christopher Reeve played ‘The Man of Steel’ to perfection. He was equally convincing as Superman in the three sequels that followed even though the storylines did not match up to his super feats. Brandon Routh acted well in Superman Returns in 2006 but was nowhere close to Reeve’s portrayal of Clark Kent/Superman—a role that began and ended with Reeve. R.I.P. Ditto for Batman, though I prefer Val Kilmer as ‘The Caped Crusader’ in Joel Schumacher’s 1995-released Batman Forever over Michael Keaton in Tim Burton’s 1989 film Batman. If you have read Batman comics, you will easily pick Kilmer as Bruce Wayne/Batman over Keaton and the two other contenders, George Clooney (Batman & Robin, 1997) and Christian Bale (Batman Begins, 2005, and The Dark Knight, 2008). Bale comes a distant second.

Ditto for Batman, though I prefer Val Kilmer as ‘The Caped Crusader’ in Joel Schumacher’s 1995-released Batman Forever over Michael Keaton in Tim Burton’s 1989 film Batman. If you have read Batman comics, you will easily pick Kilmer as Bruce Wayne/Batman over Keaton and the two other contenders, George Clooney (Batman & Robin, 1997) and Christian Bale (Batman Begins, 2005, and The Dark Knight, 2008). Bale comes a distant second.

Tobey Maguire just doesn’t become Peter Parker in the Spider-Man film series directed by Sam Raimi in 2002, 2004 and 2007. His portrayal of ‘The Amazing Spider-Man’ was as weak as Keaton’s Batman. They are both okay as long as they are both wearing their masks. Don’t ask me why.

Tobey Maguire just doesn’t become Peter Parker in the Spider-Man film series directed by Sam Raimi in 2002, 2004 and 2007. His portrayal of ‘The Amazing Spider-Man’ was as weak as Keaton’s Batman. They are both okay as long as they are both wearing their masks. Don’t ask me why.

The one-film Daredevil starring Ben Affleck who plays the suave Matt Murdock, the blind lawyer by day and masked vigilante by night, was directed by Mark Steven Johnson and released in 2003. The role of ‘The Man Without Fear’ suited Affleck but then he has no competitors. The first half-hour of the film, where a young Murdock who lives with his father, boxer Jack Murdock, in the Hell's Kitchen neighbourhood of New York City and is blinded by a radioactive substance, is worth every rupee spent on popcorn.

The one-film Daredevil starring Ben Affleck who plays the suave Matt Murdock, the blind lawyer by day and masked vigilante by night, was directed by Mark Steven Johnson and released in 2003. The role of ‘The Man Without Fear’ suited Affleck but then he has no competitors. The first half-hour of the film, where a young Murdock who lives with his father, boxer Jack Murdock, in the Hell's Kitchen neighbourhood of New York City and is blinded by a radioactive substance, is worth every rupee spent on popcorn.

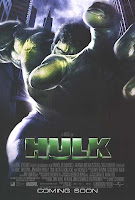

Director Ang Lee turned ‘The Incredible Hulk’ into an animated cartoon character in The Hulk released in 2003. Fortunately, Louis Leterrier, who directed The Incredible Hulk (2008) with seasoned actor Edward Norton in the lead, salvaged the character of the green giant and did justice to “Hulk is the strongest there is…” I thought Eric Bana was a trifle more convincing as Dr. Bruce Banner and his alter-ego The Hulk in the Lee film than Ed Norton. This one’s still open to debate, though.

Director Ang Lee turned ‘The Incredible Hulk’ into an animated cartoon character in The Hulk released in 2003. Fortunately, Louis Leterrier, who directed The Incredible Hulk (2008) with seasoned actor Edward Norton in the lead, salvaged the character of the green giant and did justice to “Hulk is the strongest there is…” I thought Eric Bana was a trifle more convincing as Dr. Bruce Banner and his alter-ego The Hulk in the Lee film than Ed Norton. This one’s still open to debate, though.

Iron Man, the latest in the superhero sextet, is hugely entertaining, both for its super visuals and sounds as well as the super performance by Robert Downey Jr. You might not agree with the choice of the swashbuckling RDJ as Anthony Edward Stark or The Invincible Iron Man in the two versions directed by Jon Favreau and released in 2008 and 2010, but you got to admit, however grudgingly, that he does justice to the armoured man’s role. More power to Iron Man’s heart!

Iron Man, the latest in the superhero sextet, is hugely entertaining, both for its super visuals and sounds as well as the super performance by Robert Downey Jr. You might not agree with the choice of the swashbuckling RDJ as Anthony Edward Stark or The Invincible Iron Man in the two versions directed by Jon Favreau and released in 2008 and 2010, but you got to admit, however grudgingly, that he does justice to the armoured man’s role. More power to Iron Man’s heart!