This would be my sixth review under my “First Novels” challenge and, I’d assume, a deserving entry for Friday’s Forgotten Books at Patti Abbott’s blog Pattinase, which is being handled by Evan Lewis at his blog Davy Crockett's Almanack today.

|

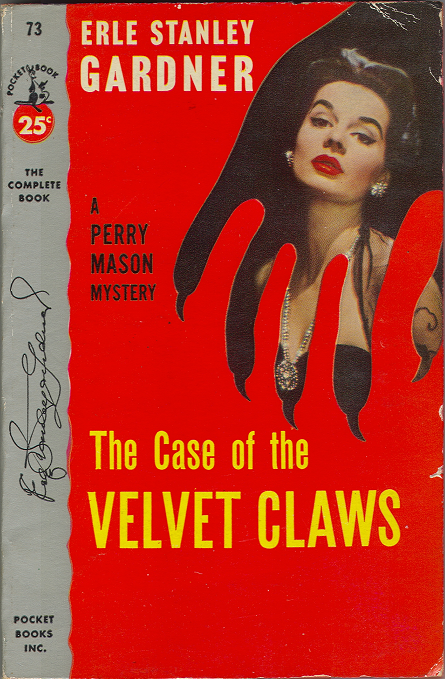

| My copy of the book. |

Elia Kazan, the renowned Greek-American filmmaker, wrote his first novel America, America in 1962 and made it into an award-winning film a year later. It was released as The Anatolian Smile in the UK.

By then, however, Kazan, who The New York Times called “one of the most honoured and influential directors in Broadway and Hollywood history,” had already produced and directed many acclaimed films like A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, East of Eden, The Arrangement (based on his book), and The Last Tycoon. He also acted in a few films including City for Conquest alongside James Cagney and Ann Sheridan.

I’m familiar with Kazan as a filmmaker but not as an author of some half-a-dozen novels, including The Arrangement which he wrote in 1967 and filmed in 1969, besides nonfiction works like Elia Kazan: A Life, his autobiography.

I was, therefore, surprised when I came across the first 1969 Sphere Books edition, pictured above. At first I thought it was a work of nonfiction; perhaps, a book about filmmaking; he has written those too. Instead, it turned out to be semi-autobiographical where Kazan gives us more or less a fictional account of a youth who spends his life in hardship and poverty and his burning desire to run away to America and start a new life. Kazan was born in Istanbul, to Cappadocian Greek parents who migrated to the US.

By then, however, Kazan, who The New York Times called “one of the most honoured and influential directors in Broadway and Hollywood history,” had already produced and directed many acclaimed films like A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront, East of Eden, The Arrangement (based on his book), and The Last Tycoon. He also acted in a few films including City for Conquest alongside James Cagney and Ann Sheridan.

I’m familiar with Kazan as a filmmaker but not as an author of some half-a-dozen novels, including The Arrangement which he wrote in 1967 and filmed in 1969, besides nonfiction works like Elia Kazan: A Life, his autobiography.

I was, therefore, surprised when I came across the first 1969 Sphere Books edition, pictured above. At first I thought it was a work of nonfiction; perhaps, a book about filmmaking; he has written those too. Instead, it turned out to be semi-autobiographical where Kazan gives us more or less a fictional account of a youth who spends his life in hardship and poverty and his burning desire to run away to America and start a new life. Kazan was born in Istanbul, to Cappadocian Greek parents who migrated to the US.

The 186-page novel has an introduction by playwright-screenwriter Samuel Nathaniel Behrman titled ‘An Effrontery of a Director.’ It is set in and around a poor village situated at the foot of Mount Argaeus in Anatolia, known as the Asian part of Turkey. I believe the period is late 19th century when the centuries-old Ottoman Empire ruled by Muslim Turks persecuted the Greek and Armenian minorities.

It is the story of Stavros Topouzoglou, a young handsome Greek and the eldest of five brothers and three sisters, who feels stifled in his large simple-minded but poverty-afflicted family. His yearning for America keeps him out of the house a lot of the time and he spends a good deal of it with a proud and fearless Armenian rebel called Vartan whom he idolises. The Turkish rulers terrorise the Armenians more than the Greeks and during one brutal crackdown on an underground meeting, Vartan is killed.

Fearing for his family, Stavros’ father, Isaac, entrusts him with all the family wealth including jewellery, rugs, utensils and clothes, and sends him to distant Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), to a cousin who deals in rugs. The obedient Stavros, bound by respectful traditions like bowing before his father and kissing his hands, agrees to undertake the “mission of hope” and sets out on a donkey.

America, America is all about that momentous journey Stavros takes, in the hope that he will do well by his family and also realise his dream of going to the ultimate land of freedom and opportunity. But, man proposes, god disposes. The young man’s journey soon turns into a nightmare. In addition to being obedient and honest, Stavros is also naïve and trusting, and for the reader infuriatingly dumb. He is set upon by a thieving opportunist who befriends him, robs him of everything, and betrays him to the law, eventually forcing Stavros to murder his oppressor. By the time he arrives at his uncle’s home in Constantinople, he is penniless; even his donkey has run out on him.

Stavros finds himself homeless and hungry, scavenging for food and doing hard jobs for survival. But does he learn his lesson? Does he realise his dream?

There is more to the novel than I have let on. I don’t want to spoil it for those who haven't read it. Elia Kazan has written a brilliant and moving story of one man’s dream and in a style that is at once captivating. I'm not sure if Kazan wrote it in English or if this is a translated work. Either way, the language is simple yet emotive, a reflection of the way it was probably spoken in rural Turkey more than a century ago. For a frame of reference, think of For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway, though not in the same way.

Elia Kazan’s narrative is also unintentionally funny as you will see from the following dialogue..

Aleko releases a sort of sigh: “Ach…ach…”

Other brothers: “Ach…ach…ach…”

Aleko: “Too much. Too much food!”

Other brothers: “Too much! Too much!”

More sighs. Then, one by one, they undo the top buttons of their trousers, and thus ease out their bellies.

Aleko: “I tell those women don’t put so much food on the table, but they don’t listen.”

It is the story of Stavros Topouzoglou, a young handsome Greek and the eldest of five brothers and three sisters, who feels stifled in his large simple-minded but poverty-afflicted family. His yearning for America keeps him out of the house a lot of the time and he spends a good deal of it with a proud and fearless Armenian rebel called Vartan whom he idolises. The Turkish rulers terrorise the Armenians more than the Greeks and during one brutal crackdown on an underground meeting, Vartan is killed.

Fearing for his family, Stavros’ father, Isaac, entrusts him with all the family wealth including jewellery, rugs, utensils and clothes, and sends him to distant Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), to a cousin who deals in rugs. The obedient Stavros, bound by respectful traditions like bowing before his father and kissing his hands, agrees to undertake the “mission of hope” and sets out on a donkey.

America, America is all about that momentous journey Stavros takes, in the hope that he will do well by his family and also realise his dream of going to the ultimate land of freedom and opportunity. But, man proposes, god disposes. The young man’s journey soon turns into a nightmare. In addition to being obedient and honest, Stavros is also naïve and trusting, and for the reader infuriatingly dumb. He is set upon by a thieving opportunist who befriends him, robs him of everything, and betrays him to the law, eventually forcing Stavros to murder his oppressor. By the time he arrives at his uncle’s home in Constantinople, he is penniless; even his donkey has run out on him.

Stavros finds himself homeless and hungry, scavenging for food and doing hard jobs for survival. But does he learn his lesson? Does he realise his dream?

There is more to the novel than I have let on. I don’t want to spoil it for those who haven't read it. Elia Kazan has written a brilliant and moving story of one man’s dream and in a style that is at once captivating. I'm not sure if Kazan wrote it in English or if this is a translated work. Either way, the language is simple yet emotive, a reflection of the way it was probably spoken in rural Turkey more than a century ago. For a frame of reference, think of For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway, though not in the same way.

Elia Kazan’s narrative is also unintentionally funny as you will see from the following dialogue..

Aleko releases a sort of sigh: “Ach…ach…”

Other brothers: “Ach…ach…ach…”

Aleko: “Too much. Too much food!”

Other brothers: “Too much! Too much!”

More sighs. Then, one by one, they undo the top buttons of their trousers, and thus ease out their bellies.

Aleko: “I tell those women don’t put so much food on the table, but they don’t listen.”